Matthew Higgins is a British architect and researcher in the field of environmental design. He is currently managing director of CODA Projects LLC, a design consultancy based in San Diego.

Design Article

Connecting The Mesas: The Case For A New Balboa Park Bridge

What this is

Design articles offer tools and knowledge that designers can use in their practice.

When & Where

All week

Tags

Design = Connection, Transformation, ResilienceDiscipline Urban, Architecture, Landscape

Examine the concept of a new pedestrian bridge that could link the Central Mesa of Balboa Park with its long-neglected neighbor to the east. Connecting the two mesas would provide an easily accessible east-west route across the entire park for the first time in its history. It would also open up opportunities to expand the cultural and recreational facilities of the park and make best use of this important public space that lies at the heart of San Diego.

CONNECTING THE MESAS: THE CASE FOR A NEW BALBOA PARK BRIDGE

By Matthew Higgins

San Diegans are proud to point out that Balboa Park is 50 percent larger than New York’s Central Park. It also contains a broader diversity of habitats than its east coast cousin, ranging from manicured gardens and visitor attractions to desert environments and wild canyons. And yet, unlike Central Park, the planners of San Diego have allowed this primary open space to be sliced and diced by major freeways and arterial routes that endanger the wellbeing of anyone reckless enough to venture across the park on foot. Where once Balboa Park was defined by its mesas and canyons, it is now a landscape of isolated zones, delineated by roads.

Balboa Park also features access restrictions that extend to more than a third of its overall area: the Naval Medical Center is for military personnel only; Balboa Park Golf Course is fenced off from the surrounding open areas; San Diego Zoo, the Japanese Friendship Garden, and most of the museums charge an entry fee. The commodification of public space, combined with a disruptive road network, results in a fractured and disjointed spatial experience.

The Legacy of History

Visitors to Balboa Park who arrive from the west have an easy journey across the Cabrillo Bridge that joins the West and Central Mesas; they experience the Prado and its associated attractions in the same way as every visitor since 1915. Travelers from the east face quite a different journey: first, they must negotiate their way around the golf course’s perimeter fence and navigate the urban racetrack that is Pershing Drive; then they find themselves on the East Mesa in an area called the Arizona Landfill, a forlorn and desolate fifty-acre field that overlooks Florida Canyon. To reach the exposition buildings on the horizon involves a slippery journey down a perilous dirt track, a game of dodge with the busy traffic of Florida Drive (no pedestrian crossings or sidewalks) to reach Zoo Place (again, no sidewalk) and then a zig-zag path through cacti and ferns to emerge, hot and disoriented, somewhere on Park Boulevard. This is a tough hike for the fit and healthy. It is impossible and impassable for everyone else.

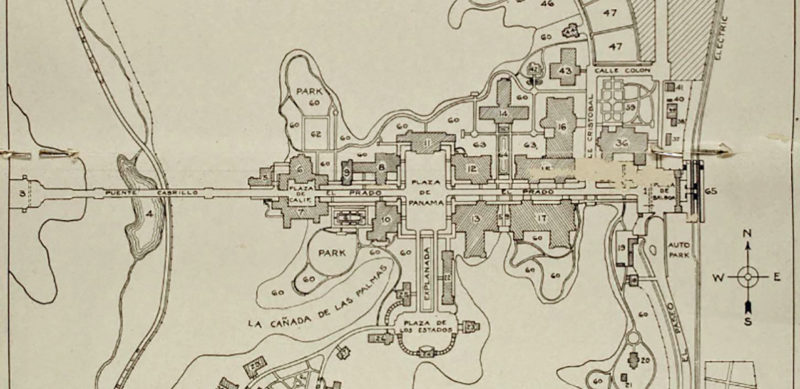

The lack of any easy route between the two mesas is an accident of history. Visitors to the 1915 exposition complex traveled over the Cabrillo Bridge at the west end of the Prado, or disembarked from the electric railway station at its east end. The electric railway ran north-south along Park Boulevard, and was used by those coming from downtown or the northern suburbs. City districts to the east of the park were largely undeveloped at this time, giving little or no incentive to create a visitor route across the East Mesa.

The railway station has since been replaced by a fountain, a landscaped berm (with no pedestrian pathway), and a rose garden at the lower level of Park Boulevard. These later additions provide a fuzzy termination point to the Prado’s grand classical composition. Visitors who walk to its east end today are obliged to return on themselves or drift northwards towards the car park. Those who are curious to see what lies across Florida Canyon are greeted with the view of a car park.

Establishing a New East-West Route

A new east-west route across Balboa Park would provide accessibility for all, allowing people to move easily from one side of the park to the other. Visitors to the exposition complex could seamlessly continue their journey eastwards across a bridge that begins where the Prado ends. This would link Park Boulevard with the East Mesa opposite, a span of around 900 feet. ‘Florida Canyon Bridge’ could be reserved for pedestrians, cyclists and trolley, with spectacular views to the north and south.

Pedestrian bridges may seem extravagant, but they have the potential to be city icons, symbolizing a new civic urbanism as well as a commitment to a healthier, less car-dependent future. London’s Millennium Bridge, with a 1,000 foot span across the Thames, is a well-known recent example.

Directly opposite the Prado is the Arizona Landfill, an area of environmental blight for almost seventy years. It is extraordinary that there has been no serious effort to clean up this site since its closure in the 1970s. Improved visitor access to the East Mesa would force the city to address a toxic, hazardous presence in the heart of the park.

What should take its place? The fifty-acre site could be used to expand Morley Field with a far greater range of outdoor sports activities. Alternatively, the city could revive a 1920s proposal for an East Mesa ‘pleasure ground’ in the manner of Frederick Law Olmsted’s pastoral design for Central Park.* An updated version might focus on Southern California’s native flora, complementing the Botanical Building and Natural History Museum opposite. The Arizona Landfill would also be an ideal location for a brand new arts complex that reflects San Diego’s aspiration to be a city of culture. Similar developments, like the Guggenheim Bilbao in Spain, show how contemporary design can draw international attention to a regional city.

The site’s strong axial relationship to the Prado offers the opportunity for a dramatic terminal vista, neatly balancing the past and future with Florida Canyon Bridge as the fulcrum between the two. Connecting the mesas would also enable visitors to begin their journey on the east side, with public parking directly off Pershing Drive. This could partially or wholly replace the existing parking by the zoo, with the latter reclaimed as green space.

In addition to unlocking the East Mesa’s development potential, Florida Canyon Bridge would provide the impetus for much-needed improvements to the Prado’s east end. Steps and a ramp could connect the existing fountain to a new public plaza either side of Park Boulevard, serving as an arrival or termination point for visitors crossing the new bridge. A public plaza could also accommodate new outside café facilities, and host the vendors and entertainers that currently line the Prado.

*I am grateful to Susan Merritt and her research on the East Mesa for this information, which can be found on her walking tour narrative prepared for 2020 SDDW.

Conclusion

Balboa Park’s existing exposition buildings are both a blessing and a curse for San Diego: a blessing, because of their exceptional beauty and the high quality of amenity space that they offer; a curse, because their Beaux Arts arrangement and architectural style set severe constraints on future expansion. By extending the axiality of the Prado to the East Mesa, this important cultural complex can continue to evolve and grow without undermining what already exists.

For all its attractions, Balboa Park is in acute need of renewal thanks to a legacy of poor planning decisions, and the challenge of introducing contemporary, high quality design within the setting of the Central Mesa. This proposal is a simple and affordable step towards addressing both issues. It is an opportunity for San Diego to create a viable future plan for Balboa Park, and to cement its status as a city of culture for the 21st century.

Drawings and renderings © CODA Projects LLC, 2021